1. Introduction

Many digital product management concepts are discussed quite controversially. However, the purpose of a product strategy is largely undisputed.

At the same time, however, there is probably hardly any other construct where aspiration and reality diverge so widely in practice: A large proportion of digital product organizations have no product strategy at all, and the vast majority of the rest at best define fragments that do not really deserve the name “strategy.”

The practical problems of a product strategy begin with the term itself. There is a frighteningly large number of different definitions of “strategy”, which leads to a correspondingly large number of more or less explicit opinions and assumptions standing side by side in product organizations as to what exactly a product strategy should be. In addition, there is a fair amount of methodological confusion, which prevents a clear view of the structure and content of a product strategy. Strategy becomes blurred between frameworks such as (product) vision, mission, objectives and key results, value proposition and business model canvas, or is pulverized in the basic principles of agile working. Finding a way out of the blur is difficult, because in the daily operational hamster wheel there is often not enough time to deal with the topic of product strategy deeply enough.

All factors together form a perfect breeding ground on which “product strategy” degenerates into something intangible. Often discussed, hardly defined, but still there somehow. Because: not having a strategy is not an option either. This post shows one possible structure to define and implement a product strategy in practice. As always in digital product management, there are different ways and preferences to reach the goal. Depending on the individual context of a company and its product organization, the approach described here must be adapted. In the end, the discussion itself is much more important than the actual format to actively address the topic and to make a conscious decision within the product organization how to tackle the challenge

2. What is product strategy?

The question of what exactly a “product strategy” is can quickly end in a lengthy philosophical discussion. Depending on the context from which the multi-layered topic is viewed, quite different aspects are important, which are reflected in different definitions and all have their justification.

From the point of view of product management, which basically includes all the essential levers of a product organization that decide on success or failure, a decision-oriented definition as proposed by Alfred D. Chandler (1962), for example, seems to be appropriate:

“The determination of the basic long-term goals and objectives of [a product organization], and the adoption of courses of action and the allocation of resources for carrying out these goals.”

Product strategy thus defines much more than functions or features.

3. The importance of a product strategy

Every product manager aims to ensure that the product solves a problem that is important to the customer (desirability), that it is technically feasible for the company (feasibility), and that the product can be used to achieve the company’s financial goals (viability) (Cagan 2017).

Technological risks are increasingly losing their horror, because there are hardly any technical limits to digital products today. In many cases, even complex functions are already available as standard components – often even for free and as open source.

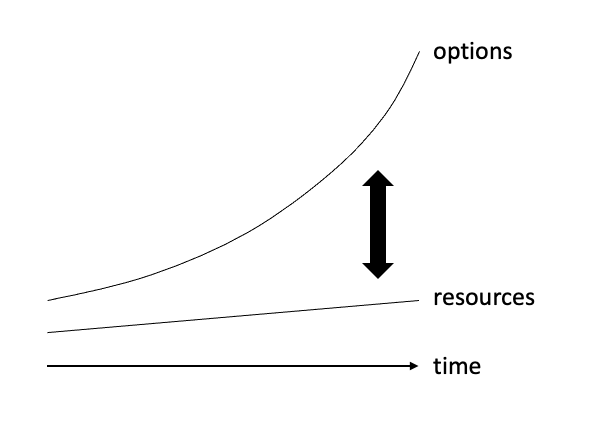

With technology becoming more readily available and more powerful, and at the same time digitization becoming more deeply rooted in target groups, more and more fragmented customer problems are becoming solvable without major hurdles. As a direct consequence, the competitive pressure for digital products is increasing. Digital product management thus faces a growing mountain of options and demands in the area of desirability, which can lead to decision paralysis.

Viability remains as the second major challenge for product organizations: With increasing competitive pressure and often existing digital network effects leading to an extreme concentration on very few winners, the financial possibilities and the resources fall behind the options, resulting in an ever-widening gap.

In this environment, it is more than ever an essential competitive factor for digital product organizations to learn faster than the competition which options bring success – and which do not. But learning always costs a lot of time, even with lean, agile methods. That’s why even (or especially) the very large digital companies focus on a few strategically important areas.

Those who act without a clearly defined combination of goal and path easily get lost in the numerous, supposedly attractive options, quickly do arbitrary things, and thus tend to reduce the all-important learning speed toward zero.

In essence, then, product strategy is a very essential necessary condition for establishing focus and direction in an organization and enabling it to make quick, efficient decisions and use scarce resources in a goal-oriented way.

4. The elements of a product strategy

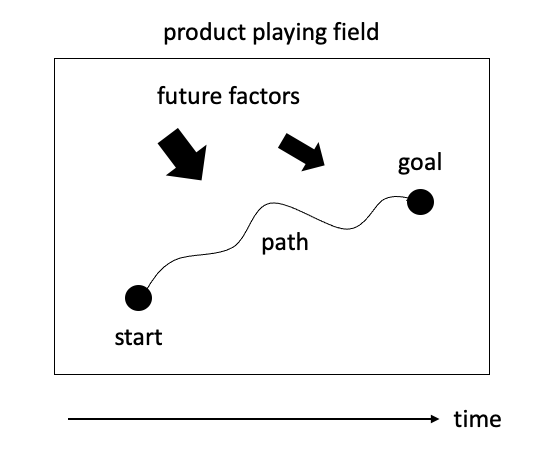

Even if the product strategy in the true sense is the defined goal and the path to it, of course no product strategy is conceivable without an analysis of the starting point. If you don’t know where your current position is, you will have great difficulty setting a goal and a path and staying on course along the way.

Since the goal lies in an (uncertain) future, it also makes sense to consider other relevant internal as well as external future factors in the process of creating the product strategy, which describe (assumed) important framework conditions for the product organization and thus have an influence on which goal or path is best chosen.

In view of the almost infinite options and simultaneously limited resources, efficient strategy development ultimately requires strong guard rails or a product playing field as the final element in order to limit the solution space from the outset and keep complexity manageable.

Since the product pitch naturally has a massive influence on the content of the product strategy, it is presented in more detail below first, before the other four elements (starting point, future factors, goal and path) are described.

4.1 The product playing field

The product playing field is of fundamental importance for every product organization, as it defines the basic positioning of the entire company – especially in comparison to the competition – for a long time to come. Because of its scope, many companies in practice shirk from defining a product vision in order to gain more room for maneuver and flexibility. But every good product needs a clear focus, and a product vision is a mandatory condition for this.

The basis for defining the product playing field is the vision and mission of the overall company, which ideally already exist. While the vision describes a relatively rough target state for the customers, the company or other stakeholders, the mission defines the fundamental way to get there.

For the fictitious company VetService GmbH, which is active in the field of animal health, the vision could, for example, be “Healthy pets and satisfied veterinarians” and the associated mission “Digitization of all processes at the veterinarian”.

Both vision and mission are by definition fuzzy, allow almost infinite options for action, and are therefore unsuitable as a product playing field for a product strategy. In order to define the product playing field, the product vision has therefore been developed as framework, which is hierarchically subordinate to and derived from the vision and mission.

There are various formats for defining a sufficiently narrow product scope via a product vision. No matter which variant is ultimately chosen, what is significant for the product strategy is the question of whether the scope of action is defined clearly enough to enable the most effective decisions possible on the content of the elements of the product strategy and not to get caught up in endless and recurring discussion loops that only cost energy unnecessarily and distract from the work that is actually to be done.

In the following, a relatively simply structured question is used to formulate the product vision:

For which target group(s) and in which context do we solve which problems with which priority in order to achieve which goals for the target group(s)?

For the VetService GmbH product, a product vision based on the vision and mission described above could look like the following, for example:

Variant A:

Our VetService product enables veterinarians to handle all necessary tasks in the veterinary practice in a highly efficient way. By this, we enable veterinarians to maximize the time they spend treating and caring for their patients.

Variant B:

Our VetService product enables medium-sized veterinary practices for all animal species with branches of 4 to 8 doctors in the EU and the USA to handle all tasks from making appointments, medical treatment, billing and payment to purchasing the necessary materials in a highly efficient manner. By this, we enable veterinarians to maximize the time they spend treating and caring for their patients.

Both variants of the product vision are deliberately defined with different degrees of freedom to show the possible range in formulating a product vision as the basis for the product strategy. How specific or non-specific a product vision is, always depends on the given framework conditions of the respective product organization. In variant B, the product organization of VetService GmbH either needs a much narrower playing field in order to limit possible options from the outset and to enable efficient decision-making processes for the product strategy – or the general boundaries, such as the regions in which the product is to be available, are already centrally specified at a higher corporate level of VetService GmbH and can no longer be discussed.

In addition to a qualitative description, suitable long-term key performance indicators (KPIs) for measuring success are essential further components of the product vision. They concretize the qualitative content and simplify the evaluation and analysis of the starting point and the definition of the target.

Unfortunately, KPIs are often carelessly neglected in the product vision in practice because they are sometimes very difficult to define. For example, it is possible to discuss intensively how best to measure the “highly efficient handling of tasks” described in the product vision from the customer’s point of view. But because the discussion about the “right” KPIs can be exhausting, it is an elementary prerequisite for cleanly defining the playing field for the product organization and, building on this, the entire product strategy.

4.2 The starting point

The starting point as an element of the product strategy contains all essential numbers, data, facts, but of course also assumptions, which are necessary to analyze and evaluate the current situation of the product organization. According to the definition of product strategy used here, which is derived from product management, other levers that are necessary to build the product must be considered in addition to the product itself.

If you have taken enough time in advance to cleanly define the product playing field with the help of a product vision and the associated KPIs (and of course measure them), it should be easy to describe the essential data for the product’s starting point. In addition, possible gaps in the product vision quickly become clear if, for example, a region (EU or USA) has not yet been addressed. In addition, there are metrics that result from the underlying mechanics of the business model (e.g., conversions or usage levels) and, finally, financial metrics that can be directly or indirectly associated. Qualitative customer feedback on the product can also be valuable in describing the starting point to scope.

Analyzing the starting point – of course, always in comparison to the relevant competition, if possible – is an effective gauge of clarity and focus within the product organization. If the aforementioned data points for the product strategy are not available quickly and transparently, it is actually always worth investing the time to build the necessary structures before taking the next steps. If the foundation is not in place, the product strategy will inevitably become shaky and the actual goal will be missed.

Established products and those new to the market struggle with reverse challenges when analyzing the starting point: A longer history brings the advantage of having more and differentiated data available, but runs the risk of losing sight of the essentials in the face of so much information. Young products, on the other hand, are inevitably more focused, but in case of doubt do not have enough measurement points to be able to work data-driven at all.

The other elements of product management are often forgotten in the context of the starting point analysis because all eyes are quickly focused on the product. However, the people working in the product organization, their skills, the available budget and, last but not least, the associated processes in operationalization are the prerequisites for being able to build products in the first place – and at the same time can only be changed in the very long term. A realistic assessment of these starting point factors is therefore a very essential and necessary condition for the definition of effective product strategies.

4.3 Future factors

Certain or assumed future events can have a major influence on decisions regarding the goal and path of the product strategy. Depending on the product and the industry, the analysis of these future factors can include quite different aspects. Typical factors include changes in competition, such as the realignment of existing competitors or the market entry of additional competitors, the development of the target market (for VetService GmbH, for example, the number of pets), general macroeconomic developments, legal requirements (e.g., regulations governing who can offer veterinary services at all), or – increasingly rare – technological leaps.

Since future factors are by their very nature predominantly uncertain, it makes sense to develop different scenarios by combining the relevant factors in their potential outcome and assigning rough probability values to them. In order to keep the complexity within limits and to concentrate on the essentials, it often helps to look back at the development of one’s own product organization and the factors that really made a difference in the past. Alternatively, empirical values on developments of other companies that have been in a similar starting position can also provide important insights.

4.4 The goal

The goal of the product strategy stands on its own, but is never conceivable without the context of the hierarchically superordinate goals as well as the strategy of the overall company. Depending on the focus of the overall strategy, (partial) goals of the product strategy may even already be explicitly specified. Most often, however, the overall strategic goals must be broken down further to the possible levers of the product organization.

Since the problem of the lack of strategy described in the introduction is not exclusive to digital product management, but in practice applies at least as frequently to the overall corporate strategy, there is often the challenge of having to define the goal of the product strategy without an overarching strategic framework. In case of doubt, the goal of the product strategy is defined before those of the overall corporate strategy, but of course should not be decided without a more intensive discussion with the corporate management.

Objectives for the product strategy always require a clear time reference and can basically be defined across all fields of action of product management: Product and resources as well as the associated processes in operationalization.

The goal of the product strategy influences the entire product organization in the long term and determines where a large part of the future time and energy will be invested. Therefore, the ambition must be to gain a sustainable competitive advantage by achieving the goal: “The essence of strategy is to perform activities differently than rivals do.” (Porter 1996). The difference can be achieved through the content of the goal (the what) and/or the defined goal level (how much of the what).

In order to make the goal tangible and to better elaborate the assumed logic for the targeted competitive advantage, it is advantageous to formulate the goal as if-then sentences: “If we have achieved goal A by time B, then we will have competitive advantage C because …”.

Depending on the complexity of the framework conditions, the set of potential goals and content orientations can be quite different. For VetService GmbH, for example, the following relevant target scenarios could arise:

- If the number of our customers in France, Italy and Spain has increased by 50% in the next 12 months, then we will have a sustainable scale advantage over our main competitor in the strongest growth markets in Europe, which will allow us to invest faster and more in further horizontal and vertical coverage of the veterinary process and, via this, to further extend our lead in the product.

- If we have realized the technical requirements for localization of the veterinary core processes in the next 6 months, then we will have created the necessary condition for the internationalization into other European countries planned in the overall corporate strategy.

- If we have reduced the average time required for the “invoicing” sub-process for our veterinarians by 75% in the next 9 months, then we will have increased satisfaction by 25% in an area that is very important for our customers in the long term and achieved a significant advantage over our main competitor.

- If, in the next 8 months, we have managed to halve the duration for a learning cycle (from the definition of the experiment based on the current critical assumptions to the execution to the evaluation and derivation of the recommended action) from 4 to 2 weeks on average, then we will be able to gain a sustainable advantage in customer satisfaction over our main competitor.

- If we have implemented an interface to our strategic partner A in the next 6 months, then we will significantly simplify the accounting process for our veterinarians and at the same time increase the cost of switching to another product in such a way that the customer lifetime value increases by 50% in the long term.

In case of doubt, it can be difficult to formulate truly measurable causalities and targets, since strategic goals are by their very nature long-term and different measures can blur in effect over time. This makes it all the more worthwhile to invest sufficient time, since only a truly intensive discussion can produce the necessary clarity about the potential leverage of different options in the product organization.

Fuzzy buzzwords frequently encountered in practice (“world-class UX”), KPIs without a clear problem definition and impact relationship (“increase net promoter score by 30%”), naked financial targets (“EUR 30 million revenues in 2030”), or concrete orders for individual features (“build a native mobile app for veterinarians”) are unsuitable as strategic goals because they are arbitrary and do not generate a clear direction. Sooner or later, bad strategic goals become visible and noticeable to everyone via pieced-together product increments.

Good strategic goals, on the other hand, have a qualitative direction through a reference to the product vision and on the basis of the analysis of the starting point, a clearly formulated cause-effect relationship and are measurable. At the same time, they give the product organization enough freedom to be able to take different paths to the goal.

In view of limited possibilities and often several possible goals, an evaluation, prioritization and selection of the goals are necessary. Which and how many goals there are depends essentially on what the framework conditions of the product organization allow for without losing focus. In case of doubt, focusing on one goal is always better than getting lost in too many goals at the same time.

4.5 The path

The path and the goal are necessarily closely linked in product strategy. Often, a sharp delineation seems difficult or the path is already predetermined by the goal. However, there is great value in consciously separating the goal (the what) from the path (the how), since on closer examination almost any goal can be achieved in different ways. With limited capacity, the key is to choose the most efficient path to maximize the overall learning speed of the product organization. If path and goal are treated as one element from the outset, there is a great danger of thinking along too narrow lines and overlooking the most efficient path.

As a basis for brainstorming the how, the goal can be reformulated as a challenge. Since many goals are not solely in the hands of the product organization, adjacent functions, such as sales, marketing and also development, usually have to be taken into account.

For the exemplary goals of VetService GmbH, the questions could be as follows:

- How can we (together with sales and marketing) manage to increase the number of our customers in France, Italy and Spain by 50% in the next 12 months?

- How can we (together with development) manage to realize the technical requirements for localization of veterinary core processes in the next 6 months?

- How can we (together with development) manage to reduce the average time required for the “invoicing” sub-process for our veterinarians by 75% in the next 9 months?

- How can we manage to halve the duration for a learning cycle (from the definition of the experiment based on the current critical assumptions to the execution to the evaluation and derivation of the recommended action) from 4 to 2 weeks on average in the next 8 months?

- How can we (together with development) manage to implement an interface with our strategic partner A in the next 6 months?

The result of the idea generation is then, of course, in many cases again a bet. Whether the selected path actually leads to the goal must therefore be continuously checked during operationalization.

5. The process of creating a product strategy

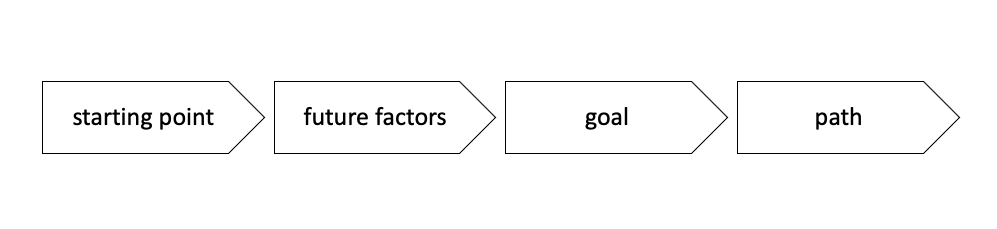

The theoretical ideal of the process of creating a product strategy would probably be to first analyze the starting point and then the relevant future factors, to then define the goal and finally, as a last step, to determine the best way to reach the goal.

Such a linear product strategy development process presupposes that all the necessary information is available from the outset and that each step can be completed cleanly before the next, but this is practically impossible. For one thing, there is far too much potentially relevant data for it to be captured completely and validly in the first place, and there are factors from the future to be taken into account that are per se uncertain or subject to change. Secondly, the process does not take place on a greenfield site, but always in a given context and a resulting bias. In particular, there will seldom be a shortage of existing ideas on the concrete what (goal) and how (path) of the product strategy.

In this environment, there is an extremely high risk that the collection of information and discussion will be controlled in advance – even if only subconsciously – in such a way that pre-existing opinions on the path and goal are merely confirmed and better strategies are overlooked. The linear process, which actually appears logical and objective, thus often supports and legitimizes a suboptimal result from the very beginning.

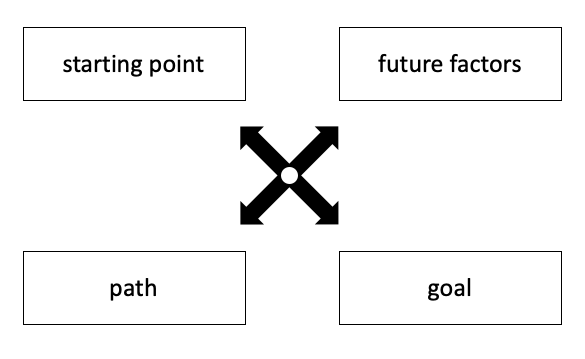

An alternative to the linear process is a deliberately heuristic one in which the elements of the product strategy, which are closely interlinked, can be considered in no fixed order and as often as desired. This allows a variety of different angles to be taken and alternative scenarios to be developed before far-reaching product strategy decisions are made.

Of course, even a heuristic approach does not guarantee that the best goal and the best path will be found, but at least the probability is a lot higher.

Thus, the complex and uncertain strategy process should not only have the freedom to iterate across all essential elements. Exploration of different options should be a fixed and regular part of the entire process, as shown in the following model.

The basic idea behind the exploratory product strategy development process is that there is a neutral point outside of the content analysis and discussion on the four elements where, depending on the context, a conscious decision is made as to which element is considered next – and this is done as long and in as rapid a cycle as possible until a decision on the product strategy has been made.

Here are three examples of an exploratory product strategy creation process for the fictitious VetService GmbH:

- There is a very attractive seeming option for a strategic partnership with another company (potential path), but where are we really at right now (starting point) and would the outcome of the strategic partnership be a worthwhile strategic goal?

- The goal of internationalization is set from the overarching corporate strategy. The path is derived relatively clearly from this, at least in terms of the scope. But what do the starting point to resources and operationalization actually look like, and what influence do they have on the path?

- Regulation for veterinarians will be deregulated in more European countries in the next 12 months (future factor). What are the worthwhile strategic objectives arising from this, and is our product organization suitably positioned for this (starting point)?

When is an exploratory product strategy development process complete? And which of the developed strategic options is the best? Every strategic decision is and remains a gut decision based on assumptions. It will never be possible to cleanly prove that a longer process or a different strategic decision would have led to better results, because multiple options cannot be tested against each other in the same context of time and content.

A natural response to deal with uncertainty is to establish comparability via risk assessments or probabilities of success, but even that can only be a pseudo-objectification in the strategic context that relates to the future. Another possibility is to think of alternative strategies from the very beginning. But such alternative plans in the back of one’s mind also harbor the danger that no strategic direction at all is then pursued with the necessary energy and the strategy becomes blurred. It seems more sensible to carry out a regular assessment in the context of operationalization once a product strategy has been defined and, in case of doubt, to change the strategy if necessary.

Defining a product strategy is a deliberate decision-making process and requires courage. Nothing is worse for a product organization than strategic uncertainty.

6. Operationalization of a product strategy

The best product strategy is worth nothing without its implementation. The problem is that implementing a strategy is once again much more difficult than defining it: “Strategy is a commodity, execution is an art.”[2] Operationalizing product strategy is therefore of very special importance, and understanding its hurdles is essential for any product organization. According to Stephen Bungay (2010), there are two of these: the “Alignment Gap” and the “Effects Gap”.

6.1 The alignment gap

The alignment gap describes “the difference between what we want people to do and what they actually do.” There are many possible reasons why the planned path is not executed in an organization: Unclear and misleading communication of the strategy between sender and receiver, too many parallel projects or unexpected events that cause the focus to be lost, own opinions, contexts and plans in the implementation teams or simply interpersonal problems.

Product organizations that follow a structured development process in defining the product strategy and involve the key people in the organization in the process can reduce the alignment gap from the outset. However, practical experience shows that over time, understanding and perception of product strategies often diverge, even in relatively small organizations, and can only be brought back together through further deliberate action during implementation. This is all the more true in deliberately loosely coupled organizations, in which largely autonomous teams work independently – but of course still have to follow the given strategic direction in order not to end up in chaos.

As a central means of alignment, Bungay (2010) proposes the principle of “briefing and backbriefing,” in which all relevant stakeholders present, repeat, and mirror the derivation and content of the strategy from their specific context at regular intervals in order to prevent possible misunderstandings through intensive and very regular communication. An essential basis for the briefing and backbriefing is a clearly documented documentation of how the strategy was developed. The format of “Auftragsklärung” can also be very helpful, in which all essential elements and argumentations from the development process of the strategy can be centrally summarized and tracked.

6.2 The effects gap

The effects gap describes “the difference between what we expect our actions to achieve and what they actually achieve.” Just like the alignment gap, is also a fundamental, empirical truth that cannot be neglected. No matter how good the implementation, the plan will not survive contact with reality. The effects gap must therefore also be considered as a fixed framework condition when operationalizing a product strategy, whereby the gap occurs on two levels at once, since both the path does not have to lead to the desired goal, and the goal does not have to lead to the desired strategic competitive advantage.

Fortunately, the answer to the effects gap is already inherent in the agile product management approach. If you divide the big picture into the smallest possible increments on the basis of a continuously maintained and prioritized list of critical assumptions and continuously test them on a hypothesis-driven basis, you will recognize deviations early on and be able to take countermeasures – depending on the analysis either via a new path to the goal, or, if the general conditions change too much, by completely realigning the goal.

Literature

Bungay, S. 2010. The Art of Action: How Leaders Close the Gaps between Plans, Actions and Results. Boston: Nicholas Brealey Publishing

Cagan, M. 2017. The Four Big Risks.

Chandler, A.D. 1962. Strategy and Structure: Chapters in the History of the American Industrial Enterprise. Cambridge: MIT Press

Mainardes, E.W., Ferreira, J.J. und Raposo, M.L. 2014. Strategy and Strategic Management Concepts: Are they recognizes by management students? Ekonomika a management XVII, 1, 43-61,

Porter, M.E. 1996. What is strategy? Harvard Business Review 74(6) 61-78,

[1] For a comprehensive review of different definitions, see Mainardes, Ferreira, and Raposo (2014).

[2] The quotation is generally attributed to Peter F. Drucker – even though it is not printed in his books and no other verified source can be found.

Photo by Willis Lam on flickr under CC Lizenz.