In our blog post „Test Angst“, we discussed the fear of product tests damaging a company’s market reputation. This time is gets actually scarier. There is a Test Angst II sitting in every one of us that is even harder to overcome. This angst triggers statements like:

- “This test person was not our target group anyway.”

- “The initial question was already a bit misleading.”

- “All people want everything for free, once they experience it live, they will pay.”

- “If we just rearrange the flow a bit, this will work.”

In these statements a fear speaks that our great idea is not as good as we thought, that all the hard work and time we already put into a project was not well spent, that we will miss predefined deadlines and financial targets. Many people who gladly pull out the phrase “fail early and often” do not find it so cool anymore, if they are the ones failing (often).

From our perspective there are two main reasons for this angst:

- People are emotionally attached to their work and unintentionally looking for positive confirmation at all times. So, feedback automatically gets a negative connotation, no matter how objective it might be phrased. “Feedback is a gift” sounds nice, but is hard to live. We are driven by confirmation bias and rather strive for validation of our idea and negate any hunch of falsifying it. So we rather read any positive results into the test than actively looking for negative feedback. This is normal and known, you can read more on that in Kahneman ‚Thinking fast and slow’.

- Even though many organizations verbally state otherwise, they still only value predictable project-plans with a predefined project effort and outcome that can be summarized in a ROI. This is so much more comfortable for budget planning, which is the real master of decision-making. The idea of a test-and-learn attitude sounds great but as long as it does not provide reliable forecasts it is sacrificed without even blinking. So, failure on your way through the Gant-chart is perceived as inherently bad for the company and the people in charge.

Think of your last product test: Did you test to convince yourself and/or others or did you test to check critical hypotheses and to become more customer centric?

An example: At a Design Thinking workshop we stressed the point of prototypes for getting interaction in a company going, no matter what the result. We did not want to build prototypes to mainly validate our product idea, hypothesis or assumption, but we wanted to honestly test it. Still nearly all participants who only spent a rough 30 minutes into creating a prototype tried to rather coerce and perusade people into liking the prototype than getting honest feedback. Although there was nothing at stake and we really stressed the point of ‘get the interaction going’.

While trying to avoid the ROI trap will in most companies feel like fighting windmills, overcoming your personal Test Angst 2 is not impossible. Once you acknowledge that it exists, you can do something about it:

- State your hypotheses clearly and well before testing.

- Always ask someone from outside your project (or even better: outside your company) to review your assumptions, testing procedures and interpretation of test results.

- Maintain a high frequency of small tests throughout the whole product development phase. This will help you to …

- … test only one hypothesis per experiment (or at least ensure that results still can be clearly interpreted when testing more than one) and …

- … file a history of learning results.

Most importantly: Only constant effort will let you fight your personal Test Angst II. Team up with like-minded people around and show with some first small initiatives what is possible. Only this can result in a growing movement in your company proving that agile learning is a true alternative to conventional decision-making. Over time a failure culture should emerge where a falsification of a hypotheses is a highly valued outcome and not a reason for punishment. This would be the end of Test Angst 2.

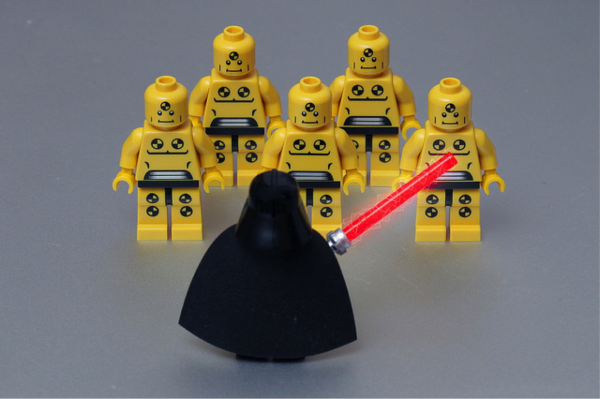

Photo by Pascal on flickr under CC License